|

|

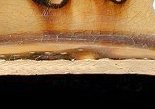

North Midlands -Type Slipped Earthenware Defining Attributes Typically, a thin, buff-bodied earthenware coated with white and dark slips and decorated with trailed, combed, or marbled designs. Generally, the white slip covers more of the visible surface than the dark slip. A clear lead glaze gives these vessels a yellowish "background" color. However, sometimes the visible proportion of light and dark slips is reversed, producing a brown vessel with yellow decorations. This ware has also traditionally been called Staffordshire-type slipped earthenware, but the term North Midlands-type more accurately reflects the broader geographic range of production of these wares. Chronology Slipware was being made in the Staffordshire region by the mid-17th century. A gradual decline in production in north Staffordshire began in the 1720s, as more attention was turned to refined stoneware and earthenware (Barker and Crompton 2007, Hildyard 2005). The first well-known Staffordshire slipware products were the elaborately decorated ornamental dishes and chargers popularly called Toft Ware, after the Toft family of potters, although many other individuals also made these vessels. They were in production by around 1660, and continued to be made into the 1720s. They are very rare on archaeological sites (Barker 2001:84; Grigsby 1993: 38; Lewis 1999: 24-27; Noël Hume 1970:136). Sherds from a Toft vessel were recovered from the Middle Plantation site in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (Doepkens 1991:153). By the last quarter of the 17th century, the production of more utilitarian trailed and combed vessels was begun and continued into the early 19th century. These pieces were used in households of all economic levels (Barker and Crompton 2007:14), as well as for use in taverns. These North Midlands-type slipwares were widely exported to America until the 1770s, although simple slipped earthenwares continued to be made in England into the late 19th or early 20th centuries (Barker and Crompton 2007; Wondrausch 1986). Many potteries produced North Midlands. Description Fabric Glaze Decoration Various techniques were employed to decorate vessels, and were sometimes used in combination on a single piece. The most basic technique is called trailing. This entails using a tube or quill to trail lines or dots of slip across a vessel. Designs included geometric or abstract patterns, flowers and animals, and human figures. Initials, words, and dates also appeared. Sometimes, simple dots predominated, especially on hollowwares. In some cases, small slip dots were placed on top of lines of slip in a contrasting color, a process called "jeweling." By the second half of the 18th century, simple straight or wavy line designs were common on flatwares. The stripes on these pieces tended to get straighter and wider through time. Many of the "Toft" dishes and chargers from the 17th and early 18th centuries had a trailed trellis-like design around their rims (Erickson and Hunter 2001:111; Grigsby 1993:46-56; Noël Hume 1970:135). Two other decorative techniques, combing and marbling, are commonly found on North Midlands-type sherds from American sites. Combing, also known as feathering, was created by drawing a pointed tool through bands of wet trailed slip, resulting in patterns of peaks and troughs. It was employed on both flat and hollow form vessels. Marbling entailed the twisting, or "joggling," of a vessel coated with wet trailed slip, which caused the slip trails to run across the piece and form abstract patterns. Dishes with joggled or marbled decoration were being produced in Staffordshire in the early to mid-18th century (Barker and Crompton 2007:14). In the 17th and 18th centuries, marbled designs were sometimes called "agate." Among excavated examples from Williamsburg, marbling is most commonly seen on flat round dishes, with blotches of green occasionally present. Marbling can also be found on hollowwares. Combed and marbled designs tended to be more elaborate and fine-grained on early pieces than on later 18th-century vessels. The designs on the earlier pieces also tend to have more of a vertical appearance, while on the later wares the combing often goes around the vessel horizontally (Grigsby 1993:17-18, 56-61; Noël Hume 1970:135). Another decoration technique involved relief impressions. The impressions came in a vast variety of forms, including dates and words. Animal and human or anthropomorphic figures were popular. These designs were stamped or rouletted onto a vessel, or created when a dish was formed over an incised press mold. Slip was then applied to the low portions of the reliefs. Sometimes the reliefs remained unslipped, or the slip was applied in a pattern that did not follow the relief. Relief decoration developed in the mid-17th century and continued in use through the mid-18th century, but was most popular in the late 17th and early 18th centuries (Grigsby 1993:39-45). Sgrafitto designs, in which a tool is used to cut through a slip coating, revealing the underlying body, are occasionally found on North Midlands -type vessels. In some cases, the body fabric consists of mixed clays of different colors (Grigsby 1993:62). Form References Barker 2001; Barker et. al. 2007; Cooper 1968; Doepkens 1991; Erickson and Hunter 2001; Grigsby 1993; 2000; Lewis 1999; Noël Hume 1970, 2001; Wondrausch 1986.

|

|

|

Thank you for visiting our website. If you have any

questions, comments, Copyright © 2002 by |

|

Click for all thumbnails

Click for all thumbnails