|

|

|

|

Bone Handled Toothbrushes Introduction Toothbrushes have become such a fundamental part of our daily hygiene routine that it is sometimes easy to overlook the fact that they were not in common, widespread use in North America until the twentieth century. It is estimated that only one person in four in the United States owned a toothbrush in the 1920s (Segrove 2010:19). Because toothbrushes wore out and were discarded quickly, they have the potential to be excellent dating tools in archaeological contexts. This essay provides a brief introduction to the types of toothbrushes that can be expected in archaeological contexts in the United States. The work of Barbara Mattick (2010), who studied toothbrushes from tightly-dated urban contexts, was used extensively in preparing this essay and in examining toothbrushes from the collections at the MAC Lab. Mattick’s dating conclusions appear largely to be upheld by contextual data from examples in the MAC Lab collection. This essay will deal primarily with bone handled toothbrushes, since bone was “used almost exclusively for the common toothbrush until the introduction of synthetic materials in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” and continued in use until around 1950 (Mattick 2010:8, 21). Humans have cleaned their teeth for many thousands of years. Historical references to implements used in dental care include cloth, sponges and chewsticks. The first bristle toothbrushes were reputedly invented in China at the end of the fifteenth century, with use beginning in Central Europe by the mid-seventeenth century and later in Western Europe (Library of Congress 2013; Mattick 1993:162). They were typically made of bone, bamboo or ivory, with coarse boar hair bristles. Toothbrushes became more common during eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but were still not in general use. France and England were major manufacturers of toothbrushes in the eighteenth century (Mattick 1993:165). Some of the early European and North American toothbrushes were double-ended, as in the 1818 print shown in the above left side of this page (Figure 1), while others looked more like paintbrushes. From the 1870s until the early 1920s, many bone handled boar bristle toothbrushes sold in America were manufactured in Japan (Segrove 2010). Toothbrush Nomenclature, Manufacture and Dating According to Mattick (2010), toothbrushes can be divided into three main components,

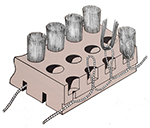

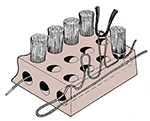

Handle Materials - While some of the more affluent members of eighteenth-century society owned toothbrushes made of silver, gold gilt, mother of pearl or ivory, the most common material used in toothbrush production was bone. Unlike wood, bone stood up well to being wet and had the added attraction of being inexpensive. Femur bones, generally from cattle, were shaped and then bleached or boiled in a weak solution of hydrogen peroxide, followed by steeping in turpentine to loosen any remaining grease (Mattick 2010:11). Although bone handled brushes continued to be manufactured into the mid-twentieth century, plastic handles began to appear at the end of the nineteenth century. The early plastic celluloid was used by 1893 and had surpassed bone in popularity for toothbrushes by the 1920s (Mattick 1993:162). The flammability of cellulose was a major drawback, however, so its use was discontinued in the 1930s. Other synthetic handle and stock materials included Pyralin, cellulose acetate and polystyrene (Mattick 2010:21). It was not until 1951 that acrylic resins were invented and transparent plastic toothbrushes became common (Virtual Museum of Dentistry 2017). Bristle Materials - Bristles were constructed of natural materials—primarily boar bristles--until 1937, when shortages were caused by the war between China (the leading source of bristles) and Japan (Segrove 2010). Synthetic materials, primarily nylon, quickly replaced natural bristles. With the invention of plastics, bristles could be affixed to the stock using injection molding (Beaver 1980). While the development of special drills in the late nineteenth century allowed the production of evenly spaced and equally sized bristle holes, the number of bristle rows does not seem to be related to date of manufacture. The 1876 White’s Dental Catalogue offered both French, English and American toothbrushes with 3, 4 or 5 rows of bristles in a variety of bristle textures (White 1876). There were two main methods—wire drawing and trepanning—for securing bristles in bone handled brushes. Mattick (2010) provides extensive explanations and illustrations for each of these manufacturing methods. It appears that both of these methods were used at the same time and bristle attachment type cannot be used as a dating indicator. Summaries of each of these methods are described below.

Mattick (2010) has divided bone handled toothbrushes into 21 types and seven varieties based on a number of physical characteristics. Each of these types has been assigned a name by Mattick, often corresponding to a state or place name. Some of these names appear to be of Mattick’s choosing, while others are period trade names. Following Gordon Willey’s typology, the places reflect the places where the earliest example of the type or variety was found. These designations are included where appropriate for each MAC Lab example pictured here, for ease of comparison with her work. The archaeological collections at the MAC Lab contain approximately 30 complete and partial toothbrushes. The MAC Lab bone toothbrush collection primarily contains toothbrushes dating to the latter half of the nineteenth century. The one double-headed example dates to the mid-eighteenth century and it was the only toothbrush that had neither wire-drawn nor trepanned bristle attachment. The bristles were attached using very thin copper wire that had been stretched across the back of the stock. It is possible that this brush was for nails, rather than teeth (Mattick 2017, personal communication). Two examples dating to the first half of the nineteenth century, from the Juvenile Justice site (18BC139) in Baltimore, were wire drawn, and like the eighteenth-century example, had thin, flat handles and stocks. One of these brushes may have also served a function other than for cleaning teeth (Mattick, 2017, personal communication). Examples whose context dates them to the second half of the nineteenth century tend to have thicker, sturdier handles, perhaps making them less susceptible to breaking. Four examples in the collection have imprinted marks bearing the names of local druggists or places of manufacture. All of these toothbrushes date to the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century or the early twentieth century. Table 1. Dates in Toothbrush History

|

|

|

Thank you for visiting our website. If you have any

questions, comments, Copyright © 2002 by |

|

whose characteristics can be useful in assigning a manufacture date and location. A toothbrush is comprised of a handle, a neck and a head

whose characteristics can be useful in assigning a manufacture date and location. A toothbrush is comprised of a handle, a neck and a head  A useful indicator for establishing a manufacture date is the relationship of the brush head and neck to the handle (

A useful indicator for establishing a manufacture date is the relationship of the brush head and neck to the handle ( In the wire drawn method

In the wire drawn method  As in the wire drawn method of attaching bristles, the rows of holes are not drilled entirely through the stock with the trepanning method

As in the wire drawn method of attaching bristles, the rows of holes are not drilled entirely through the stock with the trepanning method