|

|

Canton Porcelain Defining Attributes The term Canton porcelain has been used to refer to several types of Chinese export porcelain ftn1 over the years, as well as to the Chinese port of that name (which is known today as Guangzhou) (Madsen 1995:175), resulting in no little confusion over this terminology. For the purposes of this identification and dating essay, the term is used only to refer to late 18th- to early 20th- century blue and white Chinese porcelains, created for the North American export market.

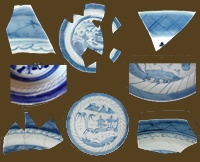

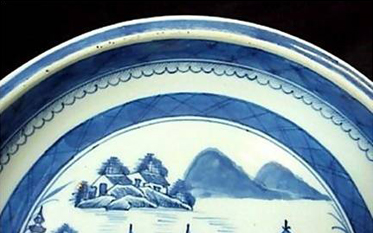

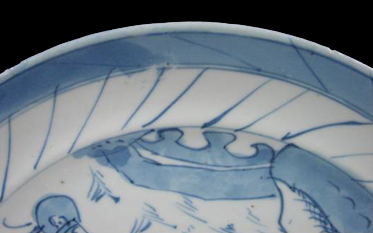

Canton porcelains are typically characterized by several variants of a border pattern consisting of a band of blue containing a crisscrossed lattice in a heavier blue, with an inner border of scallops or swags (Figure 1a). A second border pattern (Figure 1b), consisting of two parallel bands of diagonal lines that meet at an angle (Herbert and Schiffer 1975:20) is also found. Also characteristic of Canton porcelain is a fairly generic landscape design that features a building or pavilion, a bridge, willow trees, a river or stream, boats and distant mountains.

Chronology Prior to the American Revolution, Chinese porcelains arrived in the American colonies after having been shipped through England or Holland. But after the 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War, North America began trading directly with China, importing large quantities of blue and white Canton (Palmer 1976:25; Venable et al. 2000:104). As it became more affordable in the nineteenth century, Canton porcelain became more common on the tables of families of a widening range of economic levels. Jean Mudge (1986:209) states that both Canton and Nanking (another type of Chinese blue and white painted porcelain) ftn2 became plentiful after the Revolutionary War. Trade with China peaked early in the 19th century, declining after 1830 and continuing until after the Civil War (Palmer 1976:25). Madsen dates Canton porcelains in North American archaeological assemblages primarily between 1785 and 1853 ftn3 (Madsen 1995:175), disputing the shorter date spans (circa 1800-1830 and 1790-1840) assigned, respectively, by Ivor Noel Hume (1969:262) and Ann Frank (1969:85). The earliest reference found to date that references shipments of Canton is 1797, in a list of prices of porcelain in Canton written by a now-unknown Rhode Island merchant (Fuchs, personal communication 2012; Mudge 1981:259). The earliest datable pieces known at present were recovered from the wreck of the Diana, which sank in 1807 (Fuchs, personal communication 2012). Canton continued to be made without change into the 20th century (Fuchs, personal communication 2012). Table 1. Differences in Nanking and Canton Chinese Porcelain

Although Canton porcelain is still manufactured today, it was largely replaced by Japanese porcelain and by French and German china by the turn of the twentieth century (Venable et al. 2000: 104). Any Canton porcelain marked “Made in China” or “China” dates after 1891 (Herbert and Schiffer 1975:24). Description Fabric Glaze Decoration Form ___________________________ 1 This term was also used by the British when referring to 19th- and early 20th-century polychrome rose medallion porcelain (Madsen and White 2011:101). 2 Nanking porcelain, according to Frank (1969:85), is generally considered to be of a higher quality than Canton: more elaborately and carefully painted, with a lozenge diaper border with an inner spearhead border. The production of Nanking porcelain is dated between 1790 and 1850 by Frank (1969:85), although Nanking falls from fashion after about 1820 (Fuchs, personal communication 2012). 3 The T’aip’ing Rebellion disrupted the European and American export trade in Chinese porcelain in 1853 (Madsen and White 2011:102), but export of porcelain to America continued in large amounts afterwards, including a few rare armorial sets in the 1860s (Fuchs, personal communication 2012). |

||||||||||||||||||||||